Chinese Journal Review: AI investments, rural entrepreneurship, and urban-rural wage gaps

In today’s Chinese Journal Review, I summarize three articles published in the last month. The first two essays look at income inequality and urban-rural wage gaps. The latter looks at the role artificial intelligence (AI) has played in increasing Chinese firms’ integrations within global value chains.

Follow me on Twitter: @WalterAKerr

The last essay was interesting but it leaves something to be desired: the authors write that AI adoption has had a statistically significant impact on helping Chinese firms increase their integration with global value chains, but they do not quantify how much of an impact these investments have had. For example, they write that, since 2008, China’s automotives industry has been the biggest adopter of AI among all sectors evaluated. The implication is that this has helped the Chinese automotives sector capture a larger share of the global automotives market, but the authors do not attempt to quantify how much more of a share Chinese firms have captured as a result of these AI investments.

If you found this newsletter online or if someone forwarded it to you, please subscribe. This newsletter summarizes research published in top Chinese-language academic journals on topics in foreign policy, economics, technology, and international development.

Title: How industrial intelligence affects the rural-urban income gap (工业智能化如何影响城乡收入差距)

Journal: Chinese Rural Economy

Date: May 2020

Link: https://bit.ly/3hqX3Ft

Author: Liu Huan (刘欢), Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Graduate School

In this essay, Liu Huan writes that industrial adoption of smart-manufacturing technologies, including artificial intelligence and robotics, has widened China’s rural-urban income divide, but with significant differences across regions.

Industrial adoption of smart-manufacturing technologies appears to have narrowed the wage gap for urban and rural workers in China’s eastern provinces, according to Liu, whereas these innovations have widened the urban-rural wage gap in China’s west. Liu did not observe a statistically significant change in urban-rural wage levels as a result of technological innovation in China’s central provinces.

According to Liu’s research, workers from the west are the most vulnerable to technology-related job displacement and/or wage reductions for two major reasons: first, they tend to have lower education levels compared to their peers; second, given the opportunity to cut jobs because of new innovations, China’s complex household registration (hukou) system creates incentives for employers to eliminate jobs or to cut pay for migrant workers before they cut jobs for local laborers.

This disproportionately affects migrant workers from the west, who make up a significant part of China’s total migrant worker population working in the east. As of 2015, 78.2 percent of China’s migrant workforce took jobs in China’s eastern provinces, with the highest agglomerations of migrant workers taking jobs in Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu provinces. Use of industrial robots increased by an annual average rate of 36 percent from 2013-2017, with the highest rate of robotics adoption taking place among companies in eastern provinces, Liu writes. Women and older workers were the most vulnerable to loss of employment and wage reductions, she adds.

Liu predicts that the government’s Made in China 2025 agenda, which emphasizes automation and a shift from low-value to high-value manufacturing, will further exacerbate urban-rural wage gaps.

Note: The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences publishes Chinese Rural Economy. Liu categorizes the three regions according to the following groups: east (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan); central (Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henen, Hubei, and Hunan), and; west (Sichuan, Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Guangxi, and Inner Mongolia). Tibet was not included in Liu’s analysis due to limited data availability.

Title: Have rural income gaps inhibited farmers’ entrepreneurship? (农村收入差距抑制了农户创业吗)

Journal: Chinese Rural Economy

Date: May 2020

Link: https://bit.ly/2zAbwy2

Authors: Yin Zhichao (尹志超), Capital University of Economics and Business; Liu Taixing (刘泰星), Capital University of Economics and Business; Wang Xiaoquan (王晓全), Southwestern University of Finance and Economics

Dean of the Capital University of Economics and Business School of Finance Yin Zhichao and his colleagues write that income inequality significantly reduces the probability of entrepreneurship in rural areas. For every 0.1 unit increase in the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, Chinese rural household entrepreneurship levels decrease by 1.45 percent, they write.

According to their research, the proportion of rural households who were entrepreneurs in 2012 was 7.55 percent. By 2018, this had dropped to 7.49 percent. During this same time, inequality levels in rural areas increased. Large wage gaps are a problem for entrepreneurship: when farmers have less liquidity, the likelihood is reduced that they will invest their limited resources in new businesses. Less liquidity also makes new business more liable to fail. Finally, less liquidity also means farmers are less likely to invest in education or vocational training that would increase their human capital.

For their analysis, the authors compared data from China Family Tracking Surveys with county-level Gini coefficient data.

The authors recommend that the government increase cash-transfer programs for farmers, develop more inclusive financing mechanisms so that farmers can have more access to credit, and provide targeted training for farmers to improve entrepreneurship, management, and technology training.

Note: Yin Zhichao is the dean of the School of Finance at Capital University of Economics and Business and former deputy director of the China Family Finance Survey and Research Center at Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. The government-affiliated Chinese Academy of Social Sciences publishes Chinese Rural Economy journal.

Title: Artificial intelligence and Chinese companies’ participation in global value chains (人工智与中国企业参与全球价值链分工)

Journal: Chinese Industrial Economics

Date: May 2020

Link: https://bit.ly/2B0RPzG

Authors: Lu Yue (吕越), University of International Business and Economics ; Gu Wei (谷玮), Chinese University of Hong Kong; Bao Qun (包群), Nankai University

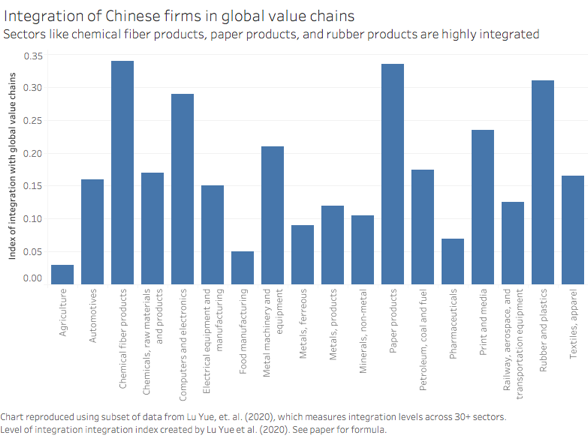

University of International Business and Economics professor Lu Yue and her colleagues write that industrial adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) has had a statistically significant impact on increasing many sectors’ integrations into global value chains.

Since 2008, the companies that process components for the automotive, rubber and plastic, metal product, and food and beverage industries have been the largest adopters of AI, according to Lu. Most AI investments in these sectors began immediately following the 2008 financial crisis. Using AI has helped accelerate these industries’ integrations within global value chains because they have used technology to increase their total factor productivity (TFP).

Lu uses data from 2000-2013 for her analysis, including Chinese customs data, enterprise-level data (with information about exports, total capital, and workforce size), as well as data produced by the International Federation of Robotics, which evaluates AI and robotics densities across industries.

During the 2000-2013 time period that she surveyed, employment levels dropped for low-end laborers in the sectors that introduced AI into their manufacturing process, Lu observed. This is because most of the AI innovations introduced during this time period replaced low-end, easily automated jobs.

According to Lu’s data, not all sectors have adopted AI at scale: textiles and wood and furniture industries have notably lagged.

Note: The government-affiliated Chinese Academy of Social Sciences publishes China Industrial Economics journal.